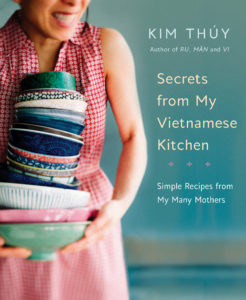

It’s probably a natural that Kim Thuy would write a cookbook. She has started a restaurant after all called Ru de Nam.

But, she says her book Secrets From My Vietnamese Kitchen (Appetite by Random House), is much more than a cookbook. It is the story of her “many mothers,” her aunts and her own mother, whose journey to safety in Canada and the U.S. was built on meals shared and enjoyed despite the trials of being refugees from their homeland, exiled in the aftermath of the Vietnam War.

Thuy is the author of important books such as Ru, Man and Vi. For her, this latest is more memoir than anything else, but there are recipes.

“First of all I hope you try the recipes because they are really easy and all the ingredients are there,” she said.

Then she says: “I’m not a chef. I write novels more than anything else.

“This book happened because we have many meals together with my aunts and with my big family. I’m 50 now and all of sudden I am realizing how lucky I am to have all these women still alive and around me who I get to talk to very often.

“For an immigrant family, it is quite exceptional that we have all our members still alive and living nearby.

“We all arrived the U.S. and Canada in different ways and at different times and so I wanted to pay homage to (the women in my family), to make a book for them and pay homage to the miracle of us being alive.”

So she turned to food.

“The Vietnamese don’t know how to verbalize emotions so we always manifest our affection and attention with food. So it is always about eating.

The common greeting in a Vietnamese home, she said, is not ‘How are you?’

It’s, ‘What do you want to eat?’ or ‘Have you eaten.’

“I also realized that in my books, I talk about food a lot. All my analogies are about food.

Because of that, she said, readers ask her questions about the food she mentions in her books.

“When I shop for food, I bump into people who ask me for recipes. I keep writing the same recipes over and over again on random pieces of paper, or in books when I sign them.

“One day I thought maybe I should write them down.” This is a bit ground-breaking.

Vietnamese people don’t have the tradition of sharing recipes, she said.

“We don’t share. The thinking is you should keep it for yourself because otherwise your neighbour could steal your husband with your recipe.

“That’s the logic and the feeling we have in our minds.”

She admits she’s probably breaking some boundaries with her book, but she’s not too worried. The recipes in her book are commonplace meals that every Vietnamese cook will know.

“At the same time you can’t find them in restaurants so that’s why I thought it would be interesting to introduce them because they are easy to make. I want the readers to really try them.”

The ingredients are available, she said. For example, fish sauce has become more common in grocery stores.

What might be intriguing for westerners is the mix of ingredients, for example, pork and shrimp. “In the western world, we never mix those together. It’s the same thing with cucumber and pineapple. You don’t mix them together.

“But try it, it’s very refreshing.” In Vietnamese cuisine, cucumbers are sautéed, she said, and the warm cukes are mixed with pineapple “and somehow the mixture is great.”

In a Vietnamese home, everything happens around the table, she said, the good and the bad.

“It is so easy for us to forget to eat together. There are so much research out there that eating together is good for your health. I was lucky to be born in a big family with many people around the table. I have learned so much from those conversations.

“You learn how to respond, to reply without being aggressive. You learn how to be able to tell your opinion without offending someone. It’s all around the table. It’s our training ground for society.”

Somewhat ironically, Thuy said she doesn’t cook Vietnamese food in her own home.

“I live next to my parents and they cook so much. It starts at six in the morning. There is so much food coming into my home. My mom has the time and she cooks so much better Vietnamese food than me, so we eat a lot from her.

“Whenever I cook, I try to cook something different. Living in Montreal we have everything. I can no longer eat only Vietnamese seven days a week.

“It has to be Indian, Italian, French, everything in between. At home we cook more Thai or Mexican all kinds.

“I love so many cuisines. I don’t think there is one I don’t like.”

She is also a self-professed omnivore.

“I would certainly eat anything. If you present it to me as something that other people are eating or is a part of their tradition, I know it’s edible so why not. You have to try different types of foods to know yourself better.

“Actually I have eaten a rat. I didn’t know what it was to be honest. I was working on a project in Vietnam and I was sent to a rice field. At the end of the day they prepared a meal. They said I should have the first bite.

“It was good. The bones seemed small and I asked what it was. They said it was a rat they had caught this morning.”

They told Thuy that rice field rats were very tasty.

The only thing she said she can’t eat are ant eggs. “They are so smelly I can’t stand that.”

Equally important is the connection this book makes with the stories of her aunts and mother.

These are beautiful, successful, older women. “I have to thank my publishers for agreeing to publish pictures of older women. When do you get to see older women in print. It’s important to see that.”

Each life story is quite compelling. “They have lived. Their faces show the time, that look, the miracle or survival.”

Thuy came to Canada on March 27 40 years ago when she was 10.

She went back to Vietnam for almost four years when she got to learn about her homeland all over again.

“It was like falling in love all over again,” She said.

She left Vietnam at a very hard time in the country’s history.

“We left at night in the dark. We were fleeing. Vietnam was very dark in my memory.” When she returned she was looking at it with the eyes of a Canadian. With that perspective, “Vietnam was more romantic and exotic to me.”

For her latest book “I just asked them to come in for pictures. That’s my family. No matter what project, they all disagree and then the next day they were washing dishes and cleaning up before opening day of my restaurant or they are giving you money.

“In this project they didn’t know what I was doing. They just came.”

One of her aunts is the vice president of huge pharmaceutical company. She flew in from Japan where she was on a business trip.

Thuy believes that those who survive after a difficult journey, feel “you have to live for all those who didn’t have a chance to do that. We all feel a responsibility to not waste the chance we have.”

And she is also grateful for the chance that Canada gave her and her family.

“You can have all the talent in the world but if you find yourself in a place where there is no place to grow, you never grow. If we had been left in refugee camp there would not be anything.

“It is because of Canada and the U.S. that anything was possible, that we could grow again. We really appreciate what we have.

“Without this country I would not have been educated and fed and encouraged. This is why our country is great. No other country would give us the freedom to try.”

In town: Kim Thuy will be at the Ottawa International Writers Festival. For more information and tickets: writersfestival.org