From a letter penned by the French sage Voltaire in 1762, to a movie poster showing a more mature, pigtail-less Anne Shirley of Green Gables, Library and Archives Canada has opened a major exhibition of 106 items that offers a take on the essence of Canada, warts and all, over the past 150 years and more.

Canada: Who Do We Think We Are is in two parts: one, situated in the main lobby of the National Library building at 395 Wellington St., shows how our sense of self has been shaped, branded and mythologized. There are facsimiles of various important things including the Nobel Prize given Lester Pearson in 1957 and plans for the Parliament Buildings. There is also an original coat of arms for the country which shows only two founding peoples. The point: it’s not all politically correct, said curator Madeline Trudeau who has been working on this exhibition for the past two years. The coat of arms is made of wood and dates to 1923. It took more than 160 hours to restore it for inclusion in the show.

This half of the show also contains an amusing scan of the mythological image of the RCMP as presented over the decades including pulp fiction and a screening of an old TV show extolling the virtues of the force, along with a selection of patriotic songs that sound somewhat dated today. Our love affair with the outdoors and winter, too, is represented as being part of the Canadian brand and mythology.

The exhibition marks Confederation’s 150 years but, Trudeau says, it is also intended to “celebrate a very important collection that belongs to every Canadian, the collection at Library and Archives Canada (LAC). One of the goals was to highlight the different collecting areas at LAC and also to illustrate the role LAC has had and continues to have in preserving our national history.

“We are presenting different versions of Canada, different visions of Canada and ideas of Canada that have existed over time. We certainly recognize that it’s more than 150 years and the collection itself acknowledges that.”

While these displays are interesting and thought-provoking, it’s the rare documents and the artifacts that really hold the attention.

Library and Archives curator Madeleine Trudeau sits in a stereotypical Muskoka chair in front of a stylized cabin all part of the exhibition Canada: Who Do We Think We Are running until March 1, 2018.

These are in the Morley Callaghan Room to the right of the main lobby and are a must see.

The very first thing you see is Voltaire’s letter, in which he decries any thought of trying to fight to keep Canada, which he very much felt was a waste of resources.

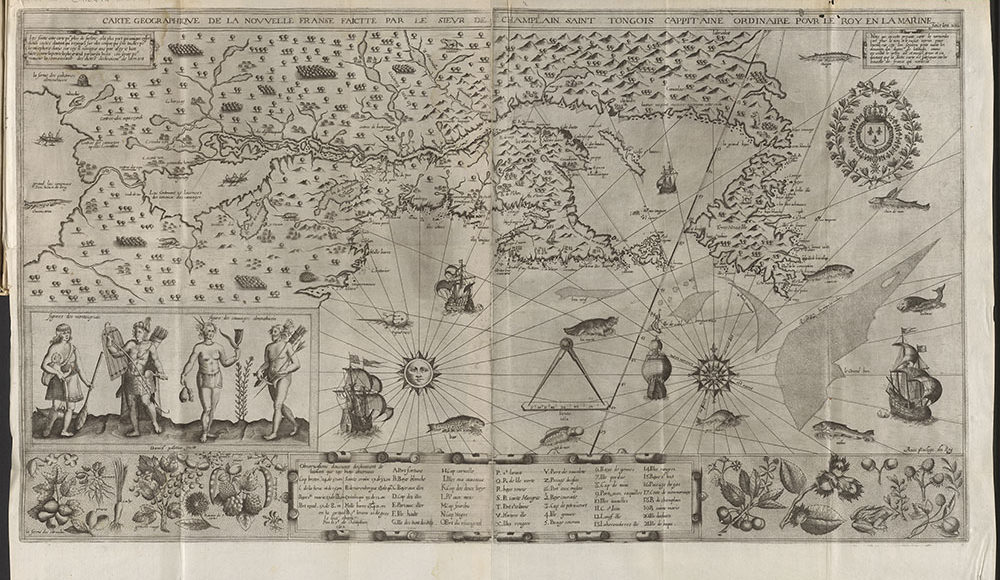

Beside it is a pitch for coming to New France made by Samuel de Champlain in an extremely rare book, published in 1613, that includes a wonderful map showing the land and the resources available for exploitation, all drawn by Champlain before being handed over to the engraver. The map was originally done in 1612 and was attached to the book in 1613. This is the oldest document on view. Trudeau says there are very few of these Champlain books that exist today, even fewer that, as this one does, have a map attached.

How this priceless book was collected is lost to time, Trudeau says, but LAC is glad to have it. The book is one of the treasures of the show, Trudeau says. But it is not the only one. Nor are all the documents as positive.

Nearby is an original of one of the first treaties signed, in 1817, involving lands in Manitoba in the west of British North America between the Crown represented by Lord Selkirk and First Nations and Metis leaders. Selkirk was a man determined to settle the west and replace the peoples who lived there with people from the British isles. That dark chapter is something that we consider today as we come to terms with Canada’s treatment of Indigenous peoples over the centuries.

“On this document you can see the totem signatures of each of the First Nations. Each one is a small animal. The document still has its government sleeve” from the Department of the Interior.

Selkirk wasn’t the only Briton who bore witness to Canada. Catherine Parr Traill was one of two sisters who came to Canada in the early 19th century and chronicled what they saw. Her only surviving journal is on view for the first time ever, Trudeau says. It is believed Traill produced seven of them. Traill talks of a landscape that is harsh but beautiful in her journals.

Nearby is a small, delicate, exquisite watercolour of a bouquet of wildflowers by Traill’s sister, Susannah Moodie. Of the sisters, Parr Traill was the more concerned about preserving the natural world she witnessed, while Moodie longed for the order of England. Moodie called Canada “the prison house,” Trudeau says. The sisters did much to create views and impressions of Canada in its early years.

Further along is an unusual presentation of Christmas cards designed by the artists of the Group of Seven. They wanted to offer a nationalistic view of the Canadian landscape that could be celebrated at Christmastime. The display also includes the catalogue prepared by the printer for ordering the cards. These are paired with views of 19th century Christmas cards showing typical Canadian scenes.

Opening measures of Caprice: Une Couronne de Lauriers, op. 10, Calixa Lavallée, ca. 1864, Iron gall ink on paper. LAC, e01163831

Walking past a small perfect plaster statue of Sir John A. Macdonald made by the sculptor Louis-Philippe Hebert you come before a cabinet with more rarities including a handwritten poem by Pauline Johnson, of Mohawk and British heritage, who was a well-known writer and performer in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In the same cabinet is a one-of-a-kind piece of a musical score written by Calixa Lavallee in 1864. The composer of O Canada was an active opponent of Confederation at the time. The research for the show uncovered this allegretto from Lavaliere’s Caprice: Une Couronne des Lauriers, op. 10 which experts on the composer had n0t seen and did not know existed. This piece of music was popular in pre-Confederation Montreal.

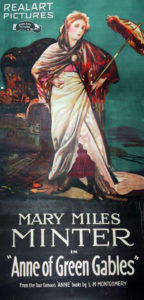

Just near the main entrance is another rarity, a colourful 1919 movie poster for Anne of Green Gables starring the American silent film star Mary Miles Minter is all that is left of the film. No copies are known to exist of the film.

Mary Miles Minter in Anne of Green Gables … from the four famous Anne books. Realart Pictures, 1919. Colour lithograph. Library and Archives Canada, e011169210. “Anne of Green Gables” is a trademark and a Canadian official mark of the Anne of Green Gables Licensing Authority Inc.

“In this exhibition there will be items people expect to see and ones they won’t expect to see. The idea more was about the versions and visions of Canada that each of these documents represent,” Trudeau says. “There are certain expectations that people have when you ask them ‘What does Canada mean?'” It aims to present amore rounded sense of Canadian history.

Canada: Who Do We Think We Are runs until March 1, 2018 at 395 Wellington St. Admission is free.