A century ago, Tom Thomson’s body was found floating in Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park. The mystery surrounding his death remains unsolved. Was he murdered or did he die by misadventure. No doubt the debate will continue for another century.

But Thomson’s legacy as a painter of note in the history of Canadian art is becoming clearer with the passage of time and much of that is due to David Silcox, the former senior federal bureaucrat, former president of Sotheby’s Canada, art historian and intellectual.

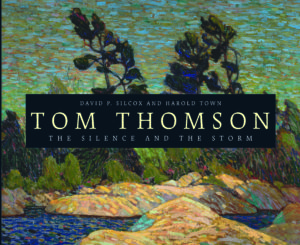

In 1997, with his great friend, the painter Harold Town, Silcox wrote and compiled a major look at the life and art of Thomson. Tom Thomson: The Silence And The Storm was acclaimed on its release.

And now, 40 years later, that work has had a major update in this anniversary year.

“The impetus for the first book was because A.Y. Jackson talked to Harold Town who had written a short piece about Thomson and said ‘You should do a serious book about him’,” Silcox said. And that’s how things get done.

“Harold talked to Jack McClelland and said he wanted to do a book about Tom Thomson and Jack said that’d be a good idea. Harold looked around for somebody to do it with because he didn’t want to do the chasing down and we had a chat about it. I was quite keen to do it. I only had one condition …” If the book was published, Town would have to accompany Silcox on any tour across Canada.

“Harold had never been west of Windsor,” Silcox said. “Finally we did do it, all the way to Vancouver. He went by train and I flew. We had a great time and stopped in all the major cities where he talked to all the people he knew of but had never met.”

Silcox is pleased with the original book, but, as with any work, there are things he wanted to amend.

“It was a different time for printing. Getting the reproductions right was difficult, much more difficult than it is now. In fact, there is too much red in the original. Hart Massey said to me after he got a copy of the book, ‘I’m just curious why is it that my Tom Thomson looks better in your book than it does on my wall.” It was because of the red.

David Silcox

Forty years ago, Thomson’s art had not been assessed as much. Frankly much of the interest in him was focussed on his tragic death, which Silcox believes was by misadventure, not murder.

So Silcox and Town set out to correct that imbalance and they accomplished a lot. Still there was more to do.

Many of his paintings were not known. “They were all over the place,” Silcox said.

In the past decade, more have surfaced from private hands in places such as Seattle, New York and Pittsburgh. Most of these were the small panels that Thomson painted in the outdoors. In the interim, Town has passed away.

“Thomson painted well over 400 of the small panels,” Silcox said. “When I was working for Sothebys, I came to think of the small panels as, not only his most important works, but also as really variations on a theme, which is a big theme for him.

“He was looking at the country and the seasons and thinking of things in a way that nobody seems to have ever considered before.”

Silcox believes that virtually all of the small panels have now been found. Many are in the National Gallery of Canada and many others are in the Art Gallery of Ontario.

There were four editions of the first book but it was out of print when Silcox was connected with HarperCollins and after a lunch and a handshake Silcox got to work on the updated edition.

“A handshake in the publishing business can be like a handshake with Mafia,” he said tongue firmly in cheek. But still, he got done to business. “I dug into it and tracked down nearly 80 Thomson paintings that had not been published before, certainly not in colour.

“And I started thinking about aspects of Thomson’s character and work which we hadn’t really focussed on,” including an exhibition of Thomson’s work at what was then known as the Art Gallery of Toronto in 1920.

“It was a highly emotional event. Basically a week later, Lawren Harris invited six friends to his house which was located just south of Victoria College in Toronto.”

That meeting led to the Group of Seven.

Influenced by a famous exhibition of Scandinavian art in Buffalo, New York in 1913, the members of the Group thought Canadian artists should be doing for Canada what the Scandinavians were doing for their countries.

“Every one drank the Kool-Aid. The country was not quite 53 years old in 1920. They felt it needed symbols and they thought they would find it in ‘The North’ which was somewhere near Lake Simcoe then and included Georgian Bay and Algonquin Park.”

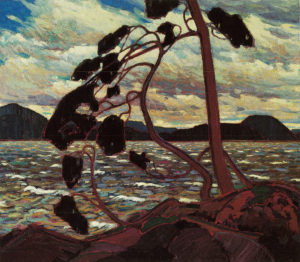

The West Wind by Tom Thomson. Photo courtesy of HarperCollins.

The further north they went, the closer the Group got to heart of Canada, Silcox said. Along the way they ignored Edvard Munch, the one radical in the 1913 show. A month after the Scandianavian show closed, the famous Armory Show in New York, which launched modern art in North American, opened. Another Canadian, David Milne, had five paintings on view there, but the Group ignored it.

“They were trying to keep anything from coming into Canada that might provide an outside influence,” Silcox believes.

When the First World War began in 1914, the momentum created by the Buffalo exhibition was suspended.

“The consequences were pretty immediate. Jackson, (Frederick) Varley and Harris enlisted. J.E.H MacDonald was busy designing war bond posters and Arthur Lismer went to Halifax to run the school of art. What that meant was that everyone stopped painting.”

Except Thomson. He had tried to enlist but was not accepted because of medical issues. Some say he had flat feet, others that he had “weak lungs,” Silcox says. So he focused on his art and when the war ended, the Group could see what he had accomplished in a few short years.

In the Art Gallery of Toronto, the walls were lined with his paintings and in the middle of the room was an empty chair.

Silcox believes that Thomson was the catalyst for the Group.

“Harris always said Thomson was a key member and had been from the beginning. Harris and MacDonald knew him really well. Thomson was a mentor to the rest.”

The last few years of Thomson’s life were spent in a frenzy of painting. It started with a patron who funded a year to focus full-time on painting and then from 1912 to 1917, he worked non-stop, Silcox says.

“He got started with Dr. James McCallum offering to support Thomson to paint full time for a year. Thomson was reluctant but eventually he accepted and by the end of the year, he had hooked himself on painting. From that moment, he started accelerating as a painter. He grabbed ideas wherever he found them. He read books, magazines on art.” He was more sensitive to what going on in the world of art than the Group of Seven, Silcox believes. .

“Toward end of his life, he was starting to change as a painter. … Some of the Group were concerned that he was getting a little more cubistic but he didn’t worry about that. I think they weren’t very attentive to the fact that that he was plucking ideas out of the air.”

Silcox believes Thomson was a great artist.

“He is durable on the strength of his painting.

“I think he is still major. There are iconic paintings such as The Jack Pine and the West Wind. and a few others like that that set him apart and above most of the other painters the Group of Seven, except some of the works of Harris and MacDonald.

“He was also moving toward abstraction. Harold wrote ‘At the time of his death a perturbed Thomson was poised at the crevice between figurative and non-figurative art’.”

Tom Thomson

Whether he would have survived the jump is a matter of conjecture, Silcox says. “The jump is to me a certainty. In 1920 the Group of Seven artists all thought the one person who could have become internationally known was Thomson.”

A key painting included in the new book is a small panel called Northern Lights. It is “very abstract,” Silcox says. “It’s just a marvel. He was getting bolder and bolder. He knew what he was doing, there is no question about that.”

These days Silcox is continuing his research into Canadian art. He is working on a project involving David Milne’s drypoint prints. And he manages the estate of Harold Town.

As for this second version of his book, he is please but … “there are changes I want to make already.”

Hear that HarperCollins?