If art and science were expressed as a Venn diagram, Juan Geuer would be the shared space in the middle.

Born in the Netherlands in 1917, Geuer was an artist from a family of artists, yet in Canada he worked at the Earth Physics Branch of the Department of Natural Resources in Ottawa.

Barry Ace. Anishinaabe [Odawa] (Ottawa, ON). Bandolier for Alain Brosseau, 2017. Mixed media. Collection of the Ottawa Art Gallery: Donated by the artist, 2017

Geuer saw science as “an activity as creative, inspired, and dependent upon perception as art,” says his bio on the website of the National Gallery, where his work is in the permanent collection. For Geuer, “the poetry in science was self-evident,” says a wall panel in a new exhibition at the Ottawa Art Gallery.

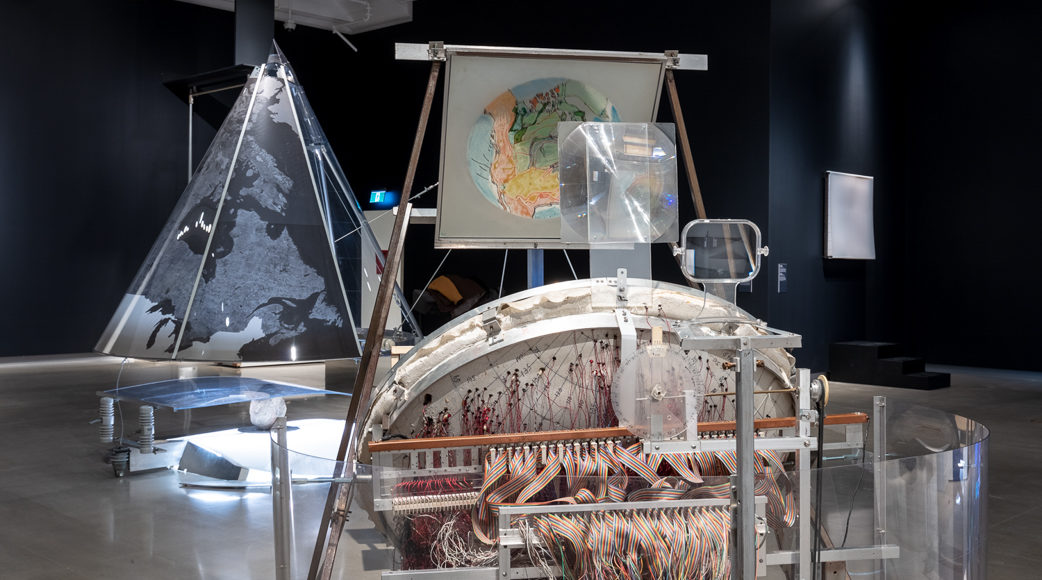

Carbon + Light: Juan Geuer’s Luminous Precision, celebrates his vision and legacy, as seen through his own art and the work of artists he influenced. Few art exhibitions involve so many tubes and wires and circuit boards. It’s interactive and almost literally crackles with invention.

The exhibition is built around several of Geuer’s installations, most of which are large and initially enigmatic, like they were built by some whimsically mad scientist. Geuer’s joy at merging scientific exploration and artistic discovery is plain to see. He was driven to have us all reconsider our planet in new ways, and to see what we’re doing to it.

Loom Drum looks like a grounded satellite, with its concave dish facing the heavens. Projected upon it by a “confluence of wires and complex circuitry” are flickering points of light, each representing one of 5,500 earthquakes that were recorded in North America between 1960 and 1989. You sit in front of the dish, and early in the 15-minute cycle it’s evident just how active is the ground beneath your feet. I half expected the floor to shift suddenly.

Darsha Hewitt (Berlin, Germany). Electrostatic Bell Choir, 2013. Electromechanical sound installation, cathode ray tube televisions, bells, pith balls, metal, electronic control system

Artwork produced at the Edith-Russ-Haus with the support of a Media Art Grant from the Foundation of Lower Saxony in Oldenburg Germany. Courtesy of the artist

Geuer wanted you to be a part of his art, to activate it by sitting on the bench or standing on a foot-sized lever. Sometimes your role is to just stand and witness, and wonder. In one work a pendulum and a dot of green laser both swing, and the dual motion, and the relationship between them and the process of circuitry and calculation that make them work, are hypnotizing — unless you’re a cat, in which case that laser dot will drive you wild.

Like that imaginary cat, many artists were transfixed by Geuer’s work, and the exhibition demonstrates how his vision fans out in different directions when imagined by others.

Germany’s Darsha Hewitt — once Geuer’s studio assistant — built Electrostatic Bell Choir. It’s a wall of older television sets, and when it senses your presence the TVs turn on and fill with static, which creates static electricity that eventually rings small bells next to the sets. It demonstrates “the limitation of our senses” to detect the “invisible forces” in the environments we’ve built around ourselves.

Ottawa artist Barry Ace weaves Geuer’s technological influence into the traditional art of his Anishinaabe culture. Ace’s Bandolier for Alain Brosseau is richly stitched with beaded motifs, and on closer inspection the flowers and other decorations are revealed as actual bits of circuitry.

Contained in the pouch of the bandolier is a tablet screen that relays the facts of a ghastly story from Ottawa’s past. In August, 1989, Alain Brosseau was walking across the Alexandra Bridge to Gatineau when he was attacked by four teenagers on a gay-bashing spree. The teens presumed, wrongly, that Brosseau was gay, and threw him off the bridge to his death.

“Alain Brousseau’s murder was a definitive turning point that galvanized and mobilized Ottawa’s queer community,” reads Ace’s telling of the tragedy. “Anyone can be a victim of homophobia or hate crimes.”

Violence endures, and even as much changes in our world, from traditional to technological, at any time only humanity can save us.

Rosalie Favell in a possum skin cloak. Photo: Maree Clark

Barry Ace is, perhaps coincidentally, a link between Carbon + Light and Wrapped in Culture, two exhibitions that could hardly be more different from one another.

In 2017 Métis artist and photographer Rosalie Favell brought together nine indigenous artists from Canada and Australia to create “contemporary versions of an Australian Aboriginal possum-skin cloak and a North American Plains aboriginal buffalo robe,” writes curator Wahsontiio Cross. The other Canadian names include Ottawa’s Ace and Meryl McMaster (Cree), and Alberta’s Adrian Stimson (Blackfoot).

Traditionally such cloaks/robes were a narrative of the wearer’s life, and into Favell’s garments are included the stories of 10 artists of different nations and generations.

The cloak and robe are magnificent. But for their perfect conditions they appear ancient in every way. The illustrations are colourful and flow fluidly across the landscapes of sewn hides, with abundant creatures both literal and mythological. The cloak and robe are hung mid-room so you can move freely around them, get close to them, even small the faint musky scent of the skins.

On the walls are photographs taken by Favell, of the artists individually wrapped in the cloak and robe. They seem to be warmly, joyfully, even ecstatically wrapped in their culture. Frankly, as a settler I envy a feeling of belonging that I don’t believe I can fully comprehend. Art, I hope, bridges such gaps.

****

Wrapped in Culture continues to Sept. 15. Carbon + Light: Juan Geuer’s Luminous Precision continues to Aug. 18. To read about two more exhibitions at the OAG — Howie Tsui’s Retainers of Anarchy and Cheryl Pagurek’s Connect — see my previous column in ARTSFILE.