Works by some 35 Canadian Impressionists will be seen in three European cities before returning to Ottawa for a major exhibition in the fall of 2020, the National Gallery of Canada has announced

Canada and Impressionism: New Horizons will feature about 120 pieces of Canadian art made between 1880 and 1930 and it will debut in Munich, Germany, this July. It will feature art made between 1880 and 1930.

The exhibition aims to showcase the versatility and ability of Canadian artists who made significant contributions to the Impressionist movement, the gallery said.

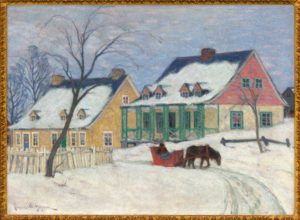

Clarence Gagnon. Old Houses, Baie-Saint-Paul (1912) oil on canvas, 52.5 × 72.5 cm. Private Collection, Toronto

The exhibition will be in the Kunsthalle München in Munich (July 19 until Nov. 2019), the Fondation de l’Hermitage in Lausanne, Switzerland (Jan. 24 to May 24, 2020) and the Musée Fabre in Montpellier, France (June 13 to Sept. 27).

When the exhibition opens at the National Gallery sometime later in the fall of 2020, it will include archival and photographic materials, works on paper and sculptures.

The intention of Canada and Impressionism: New Horizons is to introduce these Canadian impressionist artists from the turn of the 20th century to broader audiences.

The show is curated by the gallery’s Senior Curator of Canadian Art Katerina Atanassova. Many of these artists are unknown beyond Canada’s borders and little known within them.

“This is a missing chapter in the history of world impressionism that needed to be explored and explained to audiences abroad and at home,” said Atanassova.

“This is a very new thing and it has been a dream of mine for nearly a decade,” she said in an interview.

Laura Muntz. The Pink Dress (1897) oil on canvas, 34 × 45 cm. Private Collection, Toronto

In her research, Atanassova said she found a letter that underlines the importance of these artists.

It was written by Lawren Harris after his return to Canada.

“He admitted that he needed to look at painters such as Suzor Cote and James Wilson Morrice and that he needed to forget what he had learned in Europe and learn how to look at this country with fresh eyes.

“I think he was inspired by the people who came before the Group of Seven such as the Beaver Hall Group.”

Canadian artists lived and studied in France, starting in the late 1870s. They were influenced by artists such as Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and others. They took home what they learned and developed an Impressionism inspired by this country.

The exhibition is broken into seven sections from the early influence of the Barbizon School of painting to Impressionism and beyond to Modernism.

Importantly the exhibition features works by leading female artists such as Mary Bell Eastlake, Emily Carr, Prudence Howard and Sophie Pemberton.

“The two goals of the exhibition are really simple,” Atanassova said. “We are seeing around the world every other country’s Impressionism. But Canada is not in the conversation.

“This exhibition says to a wider audience: ‘Here is a missing chapter in global history of this movement and we are going to put Canadian artists on the map’.”

The show also wants Canadians to see the role of the Impressionists in the development of modern art in this country, she said.

She said Canadian Impressionism sought a way to interpret the light they found in Canada. Impressionism, broadly speaking, “is speaking the language of modern art and the awareness of what light does in the retina and how the artist captures a fleeting moment on a canvas — it is an impression of a land, an impression of time and an impression of reality,” she said.

“When the artists returned home they found a different reality and different light.” That forced them to adapt what they had learned to become more authentic to the Canadian reality.

They had to figure out how to paint snow en plein air, for example. Our harsh northern light was falling on a white surface and they saw it was blue and pink or purple.”

The exhibition will reveal that there was a much bigger discussion happening in Canadian art at the time. It was much more than the Group of Seven. In fact, three members of the Group of Seven, Harris, A.Y. Jackson and J.E.H. MacDonald, were part of this artistic discussion in 1913 to 1916 before they formed the group.

It includes artists from the west like Emily Carr to the east such as the artist Frances Jones, from Halifax, who, Atanassova said, was the earliest Canadian in Paris. She has also included many women artists whose place in the conversation is less well know such as Margaret Macpherson and Sophie Pemberton.

The galleries in Europe showing the work all have a reputation for presenting Impressionism. Beginning in Munich is important, Atanassova said, because the Kunsthalle is major gallery in the city, but also “because German audiences have never seen Canadian art not even the Group of Seven. Now we will see how Europe responds to our art.”