Jesse Thistle’s memoir From the Ashes has had an interesting impact. All of a sudden he has become sort of a go to spokesperson for the Metis people.

That is a useful platform for the PhD candidate in history with a thesis that is looking into the road allowances that caused such distress for the Metis throughout much of the first half of the 20th century. But it has also made him a lightning rod for social media trolls, so much so that he has had to change his cell phone number.

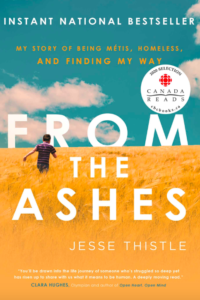

He has been surprised that his book would have such an impact and, for example, be one of the five books defended on the CBC’s Canada Reads.

“I thought only a handful of people would be interested in reading about my life. I did it as an exercise in figuring myself out and sharing a little bit about what happened to me. It’s a blessing.”

From the Ashes tells Thistle’s journey which is a story of a troubled family home with an alcoholic father. Thistle was scooped y child welfare and eventually handed over to be raised by his white grandparents in Brampton, Ontario. But he dropped out of high school and turned to a life on the streets and addictions.

He wrote: “If I can just make it to the next minute … then I might have a chance to live; I might have a chance to be something more than just a struggling crackhead.” He’s more than made it to the next minute.

He will be at the National Arts Centre on Feb. 26 in a conversation with the economist and writer Denise Chong. The evening is sponsored by the Ottawa Public Library, Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa International Writers Festival, the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation and the NAC.

Thistle thinks there is interest in the stories of Indigenous peoples in Canada in this post-Truth and Reconciliation period when he believes people are open to change.

“I tried to write it in a way that was non-accusatory. I talked about the Indigenous experience, but I didn’t say these people did this to me. I just said this is what happened. Take it for what it is. I think because of that (readers) might be able to understand the experience a little bit better without feeling guilty.”

Make no mistake he is writing about structural racism in Canada and the way our courts and health system work — or don’t work — for Indigenous peoples.

But instead of telling the tale of the racism, “I just show it” with his own journey.

Thistle has surprised himself in the way he has opened his private life up so widely. But he credits time in Alcoholics Anonymous for some of that.

“My original program was to do my steps and write down all the things that happened that made me resentful, ashamed or things that I did to other people that were bad. I was just trying to make sense of things so I wouldn’t relapse.

“I collected all these things that I had gone through. And they told my story. That’s why the chapters in the book are just fragments because that’s how I was engaging with the memories.”

As he was doing all of this, he recalled other memories and started seeing a therapist. She helped him make sense of why he did what he did.

“It all just cracked me open. I was like a clam on a beach.” It was a cathartic experience.

His book — his life — is now on the widest possible stage.

The Metis experience is not all that well known in Canada.

“The story of the road allowances it shocks people because we hear about a lot about residential schools and we hear about the poverty of the reserve system.

“Some people may know about the pass system but then when you get into the Metis experience and how we suffered the most brutal dispossession from traditional land through scrip and then the road allowances, people wonder why they weren’t taught this in school.”

It’s just not talked about.

“When I was telling my story I was thinking about how I would tell my family’s history through my own history without losing some of that context.”

The only way to do it, he decided, was to present what happened and trust that it would impart the Metis experience.

He says he gets emails from Metis people every day saying “‘Thank God, you did this. Finally we are truly represented in the national story’.”

He started learning about Indigenous history as he was emerging from rehab about seven years ago.

He then narrowed that to an exploration of Metis history and a lot of the road allowances history he uncovered in primary and secondary documents at university. This was all before he wrote the book. He is, he says, a scholar first.

He won a Governor General’s Academic Medal, a Pierre Elliot Trudeau Scholarship and a Vanier Scholarship all in the same month in 2016.

The media talked to him about his story. He began the story for one reporter with how he had robbed a store in Brampton as a teenager.

A few weeks later Simon & Schuster asking if he had anything written down about his life. So he sent the AA writings in. That led to a book contract.

The Metis people are “betwixt,” Thistle says. “We are neither them nor them. We have relatives on both sides, but we also get racism from both sides. A lot of First Nations will say (the Metis) are the original colonizers. From the white people we get, ‘What are you complaining about you didn’t endure what the First Nations went through’, not knowing our history. We also suffered a kind of dispossession which in many ways was worse.”

The Metis are also conductors of good from both sides, he says.

“We understand both perspectives. This is a great opportunity for Metis, but it is also a dangerous place to be because I don’t want to be Mr. Reconciliation and I don’t think my people do either. We have our own issues. We are our own people. It’s tricky territory.”

He says the Metis live in a cultural no-mans land “ducking shots” between two dug-in trenches.

He is closing in on finishing his PhD, but his success has gotten in the way somewhat so his wife, who is his manager, has cleared the way of outside commitments so he can finish his dissertation which is on the road allowances. It focuses on the story of his family and the various polices and practices that formed them. It follows them through the disintegration of the family in the cities of 1970s and ’80s. They were from just west of Prince Albert National Park in a place called Park Valley, Saskatchewan.

One of the most dramatic stories in his family history is about his grandmother, Marianne Ledoux Morissette. As a teenager she was a cook with Gabriel Dumont at the Battle of Batoche. When the cannons opened up Dumont pushed her out a window.

“She ran from Batoche with a group of Metis kids. She’s a hero in her own right.”

In town: Jesse Thistle will be at the National Arts Centre on Feb. 26. This is a free event but seating is limited. For more: writersfestival.org