Mischa Maisky has come a long way from his home town of Riga, Latvia in the old Soviet Union.

The 71 year old superstar cellist now travels the world as one of the most recognizable performers of the instrument.

He’ll be in Ottawa at Dominion Chalmers on Wednesday to close out the Chamberfest concert series in a performance with his daughter Lily on piano.

But before he gets here, he will have literally been around the world in a whirl of concerts in South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, India Sri, Lanka, Dubai, parts of South America the U.S. After Ottawa, he’ll head home to Belgium and then, after 48 hours, it’s off to Japan. It was a lucky break to catch him on a brief break for this interview.

He meets his schedule with “great difficulty. You don’t get used to it. It never gets easy, in fact, it is getting somewhat more difficult with age.”

Still it is impressive stamina.

“Music drives me. If you do what you really love and enjoy, it helps a lot.

Looking back on his life in music, Maisky is a direct connection to some of the greatest musicians of the 20th century.

As a teenager he was ensconced in the stimulus and intensity of the Russian school of music in the Moscow Conservatory.

“Very often when I think about it I must admit I hardly can believe I had this privilege to study with (Mstislav) Rostropovich at the Moscow Conservatory. At the same time, almost on a daily basis, I would literally bump into musicians such as (Leonid) Kogan, Shostakovich himself and many others. It’s actually quite unbelievable to me now. It’s not that we didn’t appreciate it then. We did. But now I appreciate it even more” because, basically, those times are gone forever.

That’s not to insult the great musicians of today, he said, just that things change.

As a youngster, Maisky said, his mother wanted him to be “a normal child. I was anything but.

“I was the third child in the family and my older sister (who was 10 years older) was a pianist and my older brother started as a violinist and switched to harpsichord and organ (and musicology) because of his passion for Bach.

“Educating children in music is very difficult and challenging and as much as my parents loved music, after two children they had had enough. I was supposed to be a football player.

“I love football still but I certainly don’t regret at the age of 13 1/2 (in 1961) being sent to boarding school in St. Petersburg (known as Leningrad then). I couldn’t play football any more and had to start getting serious about the cello.” He certainly got serious being named, after his debut as a teenager, the next Rostropovich by critics.

“Here we are today. I certainly wouldn’t want to change anything.”

The cello was his own choice, he said, but, “I don’t have a romantic story about falling in love with the instrument after hearing one being played while walking down the street. Maybe it happened, but I don’t remember it.

“It was just because my sister played piano and my brother played violin. It was different and the natural completion of a family trio.”

He had a dream of a family trio, but it would not happen then.

“Perhaps that’s why it became the dream of my life to have a piano trio with my children” which he now does with son Sascha on violin and Lily on piano.

He didn’t teach his children.

“They worked with other teachers. I don’t teach in the conventional sense of the word. I don’t have time and have never had the need to do it. I have managed to survive and flourish playing as a soloist for 46 years since I left the Soviet Union to start a new life.

“I feel, sincerely, that I can give more to young cellists by playing instead of teaching. When some young cellist comes backstage after a concert asking for a lesson, I reply ‘I just gave you one.’

“I learn a lot all time from listening to great musicians and not only musicians. I learn from anyone, anywhere, any time.

He then paraphrased a Russian saying. “You might be lucky to live to become 100 and if you are wise you will be learning until the day you die. Even so, you will still die ignorant.”

The more you learn, he said, the more you realize how much there is to learn.

Maisky is also fond of quoting Albert Einstein.

“Einstein was teaching at Princeton and at the end of the year, he gave students the questions for their final exam. One noticed that all the questions were the same as the last year. Einstein said. ‘Yes, but all the answers are different’. This is what happens in life. You learn and things change.”

You also understand there can be many different answers to the same question.

Why Einstein? “I like wise people. He also said, ‘There are two things which have no limitations, the universe and human ignorance. But I’m not sure about the universe’.”

The Maiskys’ concert in Ottawa is full of music from the duo’s recent CDs, recorded on Deutsche Grammophon, including the last one called Adagietto.

Included among the pieces by Bach, Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich, is a version of Pamina’s aria from The Magic Flute by Mozart.

“One of the main frustrations of any cellist,” Masiky said, “probably is that Mozart never wrote a single note for a cello solo although he did write for practically every other instrument.

“It is a mystery I will never comprehend. I wish I could meet him and find out that answer to see if my totally baseless theory has credence. That is that his wife, Constanze, had an affair with a cellist and he decided to pay all cellists back. It’s a ridiculous theory, but it is frustrating there is no sonata or concerto.”

Pamina’s aria is beautiful, he said, and it suits the cello well he believes.

When playing music not written for his instrument, Maisky said, his idea is to stick to the original as much as possible.

“If you play really great music, and I try to play only music i consider to be great, you cannot improve on the great composers. Inevitably you will make it worse.

“I choose very carefully only pieces which suit my instrument and present it from a different point of view.

“I believe most great composers were (and are) more open-minded about this kind of thing. They rearranged their own music and the music of other composers.” That may offend the “purists,” he said, but he doesn’t care.

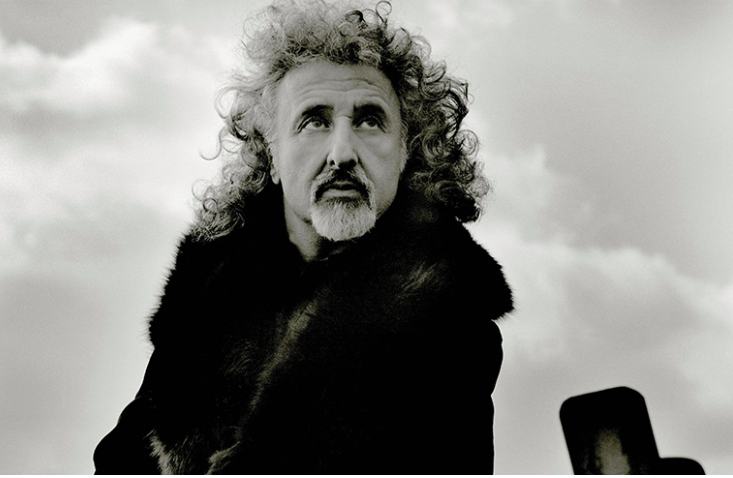

Maisky is known for his flowing locks and for wearing coloured shirts when he performs. Why?

“Why not? I started this for practical reasons. I move a lot in a concert. I use a lot of energy and I perspire. I also feel uncomfortable in a penguin outfit.

“Some people misunderstand and think I am making some kind of fashion statement, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. In fact it’s the exact opposite.

“A concert is not a fashion show,” he said. “An artist should not come on stage to show off Armani tails. What is important is the music.

“If clothing helps a musician perform well, it’s OK as long as it is respectful enough. I don’t play in jeans and different coloured socks as some esteemed colleagues do.

“Then there is a sexist element. Ladies can wear what they want. Men have to be in black. Why?”

Maybe, he said, his sartorial choice is, unconsciously, a protest against the image of classical music being stuffy, old fashioned and conservative.

That stuffiness has nothing to do with the music. Even worse, he said, it scares young people away before they get a chance to hear the music.

“They see an orchestra saluting like 100 penguins and they think this is not for us.”

Maisky has a certain allergy to uniforms and uniformity, particularly, he said, in art and music.

Perhaps that stems from from his life in the Soviet Union and his imprisonment on rather trumped up charges in 1970 in a labour camp near Gorky for 18 months. He emigrated after being released. He went to Israel and soon after started his professional career debuting at Carnegie Hall in 1973. On the outside, he also studied with one of the other great cellists of the day, Gregor Piatigorsky.

These days he plays with Lily and Sascha a lot. Lily and Mischa have been performing together for some 15 years.

“I feel an easy and natural musical connection. We both enjoy it much.

“It was the dream of my life when she was born and then two years later my oldest son Sascha was born. I told their mother that Lily would play piano and Sacha would play violin and we would travel and play together.

” My wife at the time said it would be nice but ‘Don’t hold your breath’. Very often the children of musicians don’t want to become musicians.

“My reaction was that if that was the case then my dream would be to play with my grandchildren. I can wait 40 years.”

Luckily he didn’t have to wait long. Good thing because he says they have both told him he wouldn’t have grandchildren from them, he said.

“My reaction to this was to make more children.” He has had four more with his second wife.

The youngest is four. The six year old has started on the piano and the nine year old has turned from football to piano. His 14 year son Maxim, too, has gotten serious about piano.

“Now he is seriously trying to catch up with the time he lost doing music for fun. He is now in a music school. He left home the way I did at about same age.”

The Maiskys were all together on their musical cruise from Singapore to Dubai. They all played.

“I am a lucky man from many different points of view.

“I am the luckiest cellist in world because I am the only one to study with Rostropovich and Piatigorsky. I had the incredible luck to meet Pablo Casals two months before he passed away at 97 years young. I played with him.

“I was lucky to find my (rare 18th-century Montagnana) cello 45 years ago after my debut in Carnegie Hall. I have been lucky in my partners in chamber music starting with Radu Lupu and Martha Argerich.”

Yes indeed, it is a long way from Riga.

Chamberfest presents Mischa and Lily Maisky

Where: Dominion-Chalmers

When: May 8 at 7:30 p.m.

Tickets and information: chamberfest.com