Ruth Abernethy’s life is, as she says, “in tidy little pieces.”

One of Canada’s most prolific and talented sculptors in bronze did not start her career in art school. She began in theatre in the prop shop. Her journey so far is the subject of a memoir in pictures and words called Life and Bronze. If you know the bronze of Oscar Peterson outside the National Arts Centre, or Glenn Gould near the Rogers Centre in Toronto, or Al Waxman, or dozens of other pieces of public art, you know Abernethy’s work.

She’s not to fond of the word ‘memoir.’

“A memoir feels like a summary and I don’t know that I have done that. I feel like I have written volume one of a story that is on-going.” Will she write volume two … well that’s something for another day.

“My life comes in these tidy little pieces. I did do props for 20 years from 1977 to 1997 when I did my first bronze.”

Glenn Gould near the Rogers Centre in downtown Toronto.

She started at age 17 as an assistant carpenter in summer stock theatre near her home in Lindsay, Ontario.

She got the job because, she says, “I was useful. It was what I could do. (In props) it’s the oddball things that really stump people. It’s: ‘We need a huge French birdcage and we have no money.’ My response is ‘I can throw one together out of javex bottles.’ That’s me in a nutshell, that lateral thinking that does peculiar problem solving.”

Apparently this kind of thinking and doing is a whole family pursuit. Abernethy, her parents and siblings were people who spent a lot of time thinking things up.

“I always knew I was very spatial. I just knew that. It took me time to realize other people weren’t and I had something others didn’t have. It is that lateral drift of mind, I’m not sure how else to describe it.”

What theatre provided her was a means of connecting the things she made to a bigger story.

“What I loved about theatre was this commentary that was larger than the individual. It is that collective commentary which, in my view, is what connects theatre, farming and the prop shop and sculpture. In my mind they are nicely aligned.”

And theatre became her life. She tried college for a year, but it didn’t hold her interest. She was already working in theatre, which was a job, if you could put up with the transient nature of it and the mediocre pay, that would allow you to see Canada. And Abernethy wanted to travel, plus she loved the spontaneous creativity of making something for a play from scratch.

“I was accepted into art school but it didn’t satisfy the need for human engagement. The thought of being in a studio did not feel terribly creative. In fairness, I’m not sure I was smitten by theatre as performance but I was smitten by theatre as a means to understand design.”

She worked everywhere including running the prop shop at the Manitoba Theatre Centre. Finally she ended up in Stratford working for the Festival in 1981.

For the next 16 years she worked at making the magic of theatre happen. Building statues out of styrene. Making heads to put on pikes. By 1997, she had developed her talents to an exceptional degree when her career and her life took a turn.

“The first bronze was made during a year when the Stratford Festival was being renovated. I was asked if I wanted to sculpt a fundraising indicator. They didn’t want to do a United Way thermometre sort of thing. I was asked if I wanted to sculpt a group of Norman Rockwell-esque villagers watching a tent go up.”

Those first sculptures were made of fibreglass and they were very popular. Within a few months of their unveiling, rumours of bronze started going around. Abernethy didn’t believe it, but the fundraising campaign went very well and there was enough money to do a statue.

And the prop shop problem-solver now had to figure out how to make a bronze. So she redid the sculpture out of styrene, coated it with wax and found a foundry in nearby Georgetown, Ontario that had developed the technique of going to bronze from a styrene-wax sculpture.

And for Abernethy, “the drawbridge” to a career as a bronze sculptor “went down.” And out she went like Bilbo Baggins not knowing where the road was leading.

She says she didn’t really like working with wax at first, but she says she has come to understand and appreciate it.

“I fell into this career. It seems to me (now) I was destined for this kind of life. I feel very honoured.”

She is a woman working in a male-dominated field, but that doesn’t faze her.

“I have often wondered if it is harder, but I have no real way of knowing that. I like working with men. I have always worked with men.

“I’m not really interested in saying it’s harder being a women. There are certain assumptions that do work against you yes,” but so what, she says.

“I wish I was a better negotiator, but you want to make these things happen. I look through the book and realize the number of projects that would have been priced out of existence had I bargained further.”

So compromises have been made.

“There is may be assumptions about how lucrative it has been for me and I have to say ‘Are you kidding?’ I am the value-added.”

But it all has been worth it.

Unveiling Oscar with the Queen and Prince Philip.

She loves the fact that people love her pieces. The Oscar Peterson statue is almost always surrounded by smiling faces.

“That’s the goal. I adore them, I adore that they are out there engaging with people sharing their stories. They are giving people moments to remember. One thing that I love: These are like permanent performances. Oscar never changes but we do. It’s great that 1,000 loving hands touch these sculptures.

“When people are standing there with Glenn Gould or Al Waxman, you are having a moment with Glenn Gould and Al Waxman. I’m not supposed to be in the way. This is ‘I’d like you to meet Glenn Gould’.”

Abernethy always has projects on the go. Recently her statue of Lester Pearson was unveiled at Castle Kilbride in Baden, Ontario as part of a series of bronze portraits of Canadian prime ministers called the Prime Ministers Path.

She has finished her bronze of Queen Elizabeth, done in recognition of 65 years on the British throne. The site for the sculpture is being prepared.

“She exists in bronze and I think she’ll be spectacular,” when she is unveiled.

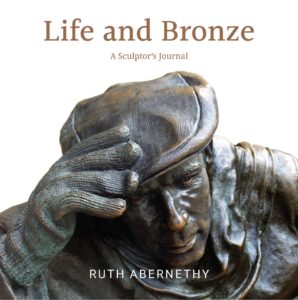

Life and Bronze: A Sculptor’s Journal

Ruth Abernathy (Granville Island Publishing)

In Town: The author will be at Galerie Côte Creations, 98 Richmond Rd. on July 9 at 3 p.m.