On the 14,000th day, give or take a few thousand, the Ottawa Art Gallery and its decades of supporters said, “Let there be light.”

And the light was good, indeed glorious, for it was natural light, and it poured into the exhibition spaces as it never had before, not into the old, venerable building with its lack of windows, but into the new one, built on so much pushing and so much agitating by so many people for so many years.

It’s difficult to not be exultant about the new Ottawa Art Gallery. The building is bright and beautiful, and the expansive inaugural exhibition, We’ll All Become Stories, looks at art created in the region over 6,000 years, which is only slightly longer than it took to align the political funding and priorities behind a cultural institution the city sorely needed.

The old building, Arts Court, was originally a courthouse, a seat of government, a home for bureaucracy — the opposite of art. It was solid and stolid, but cramped and inflexible and, on the inside, sorely lacking in light.

The new gallery, built around and above Arts Court, has more than 55,000 feet of “programmable space,” every foot of it purpose built for the exhibition of, and the enjoyment of, art. There are large spaces, moveable walls, and high ceilings with grand panes of glass. Light pours in from every direction. Even old Arts Court itself is less gloomy, as a window has been punched into the main floor corridor.

Light unveils in ways that are obvious and surprising, permanent and temporary. What a treat is the John Ruddy Cube, the wire-enmeshed building block that fronts onto Mackenzie King and is bathed in shifting, soft colours. I drove past late one night and it looked like a giant box of pink macaroons. Yum.

A soft and briefer light glows indoors, inside the cast-resin beaver lodge built by Ottawa artist Anna Williams, which is on display only to May 14 before it leaves for a tour. Three bronze beavers sit around a life-sized lodge, each translucent twig and branch cast by Williams from real sticks that had been gathered and gnawed by real beavers. It’s called Canada House, and it seems both rugged and fragile, both enduring and transient. It speaks to a nation that rose from the wild and owes a great responsibility to it.

The inaugural exhibition spreads across every available exhibition space, just as it spreads across almost seven centuries of artistic production and development, from ancient artifacts to commissions created for the exhibition.

This is a 6,000 year old spear point. Photo courtesy Canadian Museum of History, Artefacts

Oldest is a spear point made c. 6,000 years ago, of copper mined near Lake Superior and evidence of advanced trade routes along the Ottawa River at the time.

The finely wrought point, gracefully softened by six centuries of patina, is in the technology section of the exhibition, though like everything in the show it could be in the largest section, titled Bridging. The years between the manufacture of the spear point and, say, the joint installation of photography and aerial video by father-and-son Jeff and Bear (Witness) Thomas, commissioned for the gallery’s launch, are bridged by common impulses — to adapt and survive in the world around us, even as that world has changed in many fundamental ways.

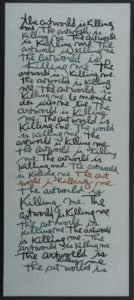

Art — in this case the art of the place now known as Ottawa — spans the centuries, races, cultures, genders, media and styles. In textiles, there are Anishinaabe artist Barry Ace’s five Hudson Bay blankets, bedecked with emblems of fire, beaver, canoes, the Thunderbird, all representing the Great Lakes and the waters that “for millennia . . .served as veins of travel, economy and recreation. . .” Another work in textile is more idiosyncratically personal. Michele Provost’s embroidery, titled Artist Statement, wryly reads “The art world is killing me,” over and over again. Does Provost’s characteristic acerbity echo to one floor up, in Pat Durr’s neon sculpture with its garishly glowing words “Culture Trash”?

Michele Provost’s embroidery, Artist Statement. Photo courtesy Ottawa Art Gallery

Art leaves much interpretation to the discretion of the viewer — finding your own way to revelation is one of the great gifts of art. Photographs in the exhibition include an allegorical self-portrait by Meryl McMaster, in which she has bee-decked herself in a stovepipe hive of a hat, and an arrangement of aluminum-printed images by Leslie Reid, which may be a memorial to her father, or to an Ottawa airbase, or to the land, or to a way of life, or to all of the above.

Such works speak resonantly to the exhibition title, for we do all become stories, however we tell them of ourselves in the contexts of our culture, our families, our own experiences. We can feel the presence of Lynne Cohen in her room populated only by sparse furnishings and “trees” of hats, for the photograph sprung from her experience. We feel the latent angst of Max Dean in his tree-topped installation — his memorial — to this late mother. We feel the history in Greg Hill’s Cereal Box Canoe, in Annie Pootoogook’s simple and influential domestic scene of the far north.

We’ll All Become Stories is our story, the story of Ottawa and the people in it, and the people who were on this land before there was a city, before “Ottawa” was a word.

On a recent Sunday afternoon the gallery was crowded with people, admiring the architecture, strolling the exhibition spaces, supping in the new café. This is a building that we all can use, a gallery that we can all be proud of. After decades of lobbying, our cultural ambition has, finally, seen the light.