The duality that was Paul Klee, and the balance it must have given him, are revealed with a stroll through the new exhibition at the National Gallery.

Klee, the Swiss-German master, had a prodigious work ethic and even in his final years, when incurable illness wore him down, he produced hundreds of works.

He worked obsessively to understand how he could speak as an artist. While teaching at the Bauhaus from 1921 to 1931 — his most productive period, when he produced thousands of drawings — he “reflected on art theory and explored colour, rhythm, geometric construction and movement, resulting in more than 3,000 pages of manuscripts, diagrams and drawings.”

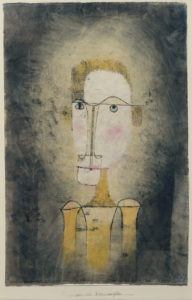

Paul Klee, Portrait of a Yellow Man, 1921, watercolour, transferred printing ink and ink on paper mounted on cardboard. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Berggruen Klee Collection.

He was methodical and exhaustively catalogued every piece he created — along with routine aspects of family life. His son Felix Klee once said in an interview that in the first two years of his life, his father “recorded my weight, what I ate, my first words, my moods, my reactions and my gestures.”

Such documentation likely grew from Klee’s knack for arithmetic and fondness for precise bookkeeping. He once said “bookkeeping is fun, it whiles away the time” — which could lead one to think he wouldn’t know fun if it whopped him on the head with a leather-bound ledger.

Yet despite his systematic and fastidious work habits, Klee knew fun, and it runs playfully, wittily through the exhibition. The Berggruen Collection from the Metropolitan Museum of Art is not all humorous — Klee did live through a world war, and the inexorable march toward a second one — but his sense of humour was “always present,” says gallery curator Anabelle Kienle Ponka, “and it goes all the way through, even when he’s sick.”

The humour comes early in the 75 drawings and paintings, and it’s abetted by the gallery. A 1919 painting on fabric is of Klee’s tomcat. “Hello, I’m Fritzi,” says the wall label, one of several posted throughout the exhibition to spare children the abuse of hearing adult artspeak. Klee “painted me next to an orange sun that matches my spots,” the label reads. Animals abound along the walls, from a pride of lions (“Take note!” is the ambiguous title) to another of a chicken and an egg (insert your own joke here).

There’s adult humour too. Near the lions and chickens is a fantastical portrait of a helmeted woman, and Klee may have been been, the label says, “poking fun at his wife Lily, whom the artist teased for her penchant for astrology.” Next to the tomcat is a small painting of a “pair of hypocrites,” two forms that seem to be . . . ah, well, viewers can interpret its Inferno-esque contortions for themselves.

Perhaps this versatile wit kept Klee level during his years of obsessive work, of being “very methodical,” Kienle Ponka says, “and at the same time never losing this kind of immediacy and this approach to art-making that is whimsical and humorous.”

The approach survived dark times. The Klees lived in Germany during the First World War. Klee was never sent to the front, because, Fritz said, Lily “pulled strings” and had her husband sent to the relative safety of a flight school. He had time to paint and, showing his career-defining interest in experimentation, he started to paint in aircraft linen.

“After a plane had crashed and the dead had been removed,” Fritz said, “my father, armed with scissors, would rush to the field and cut off pieces of the linen with which the planes were then covered.”

Paul Klee, Cold City, 1921, watercolour on paper mounted on maroon paper mounted on cardboard. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Berggruen Klee Collection.

After the war came the Bauhaus years, and Klee flourished. Yet the tenor of German life was sinking into National Socialism, and Klee was declared a degenerate. (As with his contemporary Otto Dix, he found that prior military service was no shield when extremism shed its populist cloak.) Klee was somewhat oblivious to the changing times but “as always,” their son said, Lily “had the wit to sense which way the wind was blowing,” and she arranged for the family emigrate to Switzerland.

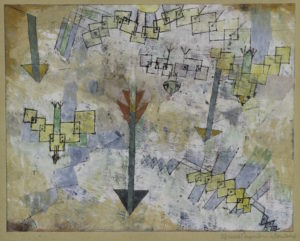

Klee died there in 1940, after years of advancing illness. What a light was snuffed out on that day, and how it illuminated the early 20th century’s grand, expanding vision of what art could be. Klee triumphed in surrealism, cubism and expressionism, from pure abstractions of joyful colour to grim allegories, such as Birds Swooping Down and Arrows, drawn in 1919 after he watched those planes crashing into the ground.

He also did portraiture, including 1921’s Portrait of a Yellow Man. It’s the personification of Klee’s quip that “a line is simply a dot that went for a walk,” as a few straight and a few curved lines intersect into a figure of striking presence. It is a symphony of simplicity, and in it one can almost hear the Bach and Mozart that Klee so loved.

It’s enough to get any child interested in art, and hold their attention for a lifetime.

The Bergrruen Collection from the Metropolitan Museum of Art continues to March 17 at the National Gallery of Canada.

Paul Klee, Birds Swooping Down and Arrows, 1919, watercolour and transferred printing ink on gesso on paper mounted on cardboard. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Berggruen Klee Collection.