When Nadia Myre was putting the title on the exhibition of tondos called Meditations on Black Lake, she says she was thinking about looking at a body of water from above.

“I was thinking about what would it look like if you were a spirit looking down on the earth and having that kind of bird’s eye view of the world. I was also thinking about theoretical bodies of water where all this human activity emerges from.”

She produced a series of eight images in 2012 and five of them now are included in a show at the School of Photographic Arts: Ottawa (SPAO) Gallery on Pamilla Street just off Preston near Carling Avenue.

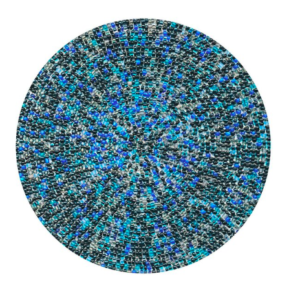

One of the tondos created by Nadia Myre on view at SPAO.

Myre lives in Montreal where she was born and raised but she has roots in the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg First Nation in West Quebec.

She is a major photographic artist and has won several awards for her work including the 2014 Sobey Art Award for artists under 40 and the Banff Centre’s Walter Phillips Gallery Indigenous Commission Award. She’s is collected in major galleries including the National gallery of Canada. So this is a rare opportunity to see her work in a small space.

Meditations on Black Lake will be on view until March 6, 2020.

This was the first of four similar series. One is called Meditations on Red, and is a striking look at the colour.

When she makes their tondos it starts with beading. She connects seed beads, which are tiny with brick stitches but they blow up into something quite interesting artistically.

“When I was making them, I was thinking a lot about painting, and that if I was a painter how would I go about painting with beads.”

Once assembled into spirals that are about five inches in diameter, Myre scans the beaded wheels instead of photographing them with a camera.

“Something I really appreciate about the scanner is that it has a really shallow depth of field.” The entire object is brought into sharp focus, she said, because the lens on a scanner is always looking at what is being scanned. She added that the light is continuous throughout with the scanner as it moves across the object.

The result are sharply defined but mystical images. Each one is also very different in appearance despite the fact that the same palate of colours was used.

This steel basket created by Nadia Myre is on view at Pimisi LRT station. City of Ottawa.

In this series, Myre was interested in building it as she went.

“I was working with it in my hands, connecting the pieces with a brick stitch. I was being contemplative. Sometimes as an artist you have an idea and you have to go and execute the idea.

“This was different. I was just going to bead. I wanted to resist working in a pattern and so it’s really about chance mostly, making different variations of colour in a mix.”

The random nature of the process appealed to Myre.

“The brain is hardwired to recognize pattern and to want to make patterns. I let these pieces be abstract moments and reflections and working within a similar colour range and then changing colours by taking one mix and adding more of something else. There was a continuous build throughout the series.”

How did she know she was finished. “Often the thing that told me I was done was strength and time. I was also working towards a deadline.”

Birch trees by Nadia Myre help form a fence at Pimisi LRT station.

Myre’s family history informs her art practice, she said.

“I was born in Montreal. I did have family roots in Kitigan Zibi, but I don’t know what is left of the family there. For sure there are cousins but I am not close with them.

“My mom was part of the assimilation program and taken off reserve. She was put into an orphanage and into the child welfare system. Her parents were not married so her grandparents didn’t have say even though they were taking care of her.”

That family history is “is predominant. It’s the biggest thing I am saying in my work. How do you identify as an Indigenous person when you aren’t born on a reserve. and don’t have the language. The culture is torn away from you literally.

“We have status but what does that mean.”

The state the obvious: Beadwork is very much part of Indigenous culture and circles are important symbols as well.

But she’s not just work with beads in this way.

This 25 foot Eel by Nadia Myre is a Pimisi LRT station.

“I have many ways of working. I do bead work that’s on a loom. I have different types of looms I’m making sometimes to make circular beadwork.

In 2014, when she won the Sobey award, she was also a bust artist.

“I think I was working hard anyway. It made me work harder.

“You are just trying to build your life as an artist and anytime you have recognition, or exhibitions, or moments when you get to share your art, your ideas and your practice it’s a privilege. It did move things into a different gear. One I am happy to continue.”

Myre works in many different disciplines.

“I have been working quite a lot in the last few years doing public art work. I finished a big commission for the city of Montreal which is looking at the 1701 peace treaty between the French and the Indigenous peoples.” This is large bronze sculpture was installed last fall.

In Ottawa, you can see her art at the Pimisi LROT station.

There are three works there: a 25 foot stainless steel eel, a large steel basket down and a metal fence with the shape of birch trees embedded.

She did do a Masters of Fine Art in sculpture, but is she a sculptor?

“I am interested in installation and how to occupy space. That’s something I do well, understanding spatial relationships.”