“It’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard rain a gonna fall.”

And so you might be humming as you leave the new exhibition of war art at the Canadian War Museum, if you’re familiar with the Bob Dylan song, A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall. Dylan’s bleak track is referenced in the title of a work that vividly upends what many people may expect “official war art” to be.

Canada has officially been sending war artists into conflict zones for a century, and the roster includes notables such as A.Y. Jackson, Alex Colville and Pegi Nicol MacLeod. It seems reasonable to suggest that many people, if they think of official war art, envision something that is stylistically traditional, perhaps even fusty and, well, official.

The notion fails, of course — Colville’s paintings of concentration camp victims at the end of the Second World War were modernist nightmares, for example — yet it’s always a thrill to see an artist breaks ranks, as does Mark Thompson in Canadian Forces Artists Program — Group 7.

Thompson, an Ottawa artist, was deployed in Kuwait, “flying in at night over the desert dotted with methane flames atop the oil-well derricks . . .” He works with glass, as seen in his public installation Cube/Lattice/Sphere/Wave along Rideau Street. At the War Museum, he begins with realist paintings of concrete bunkers, or “blast shelters,” reproduced in kiln-fired enamel on glass plates, which creates the curious effect of what from a distance look like photographs looking more and more like paintings as you get closer to them. The perception of war, no doubt, likewise changes with propinquity.

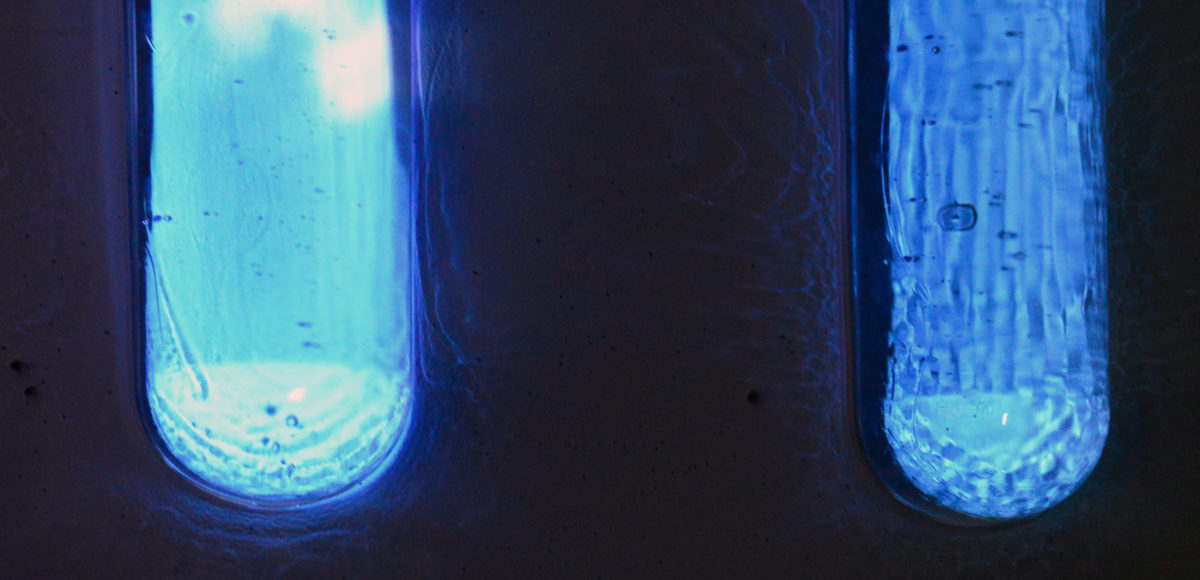

But it’s in two other installations where Thompson excels. His Book of War is a half-dozen books cast in glass and laid open on wooden lecterns. Inside each book plays a looped video of a fighter jet tearing across the sky, though it seems to be the sky that’s moving. It is a beautiful object, built around a weapon of awesome, terrifying power.

Then comes Hard Rain, and it is, indeed, a-gonna fall. Fifteen aerial bombs are made of cast glass, and through them runs a looped video of azure blue and cloud white, as if the bombs are plummeting toward ground and humanity below. It is, again, a beautiful and terrible thing, and a compelling example of what contemporary war art is today.

Ship’s Wake, # (1-16), 2016–2017 by Ivan Murphy. Oil on wood panel. From the collection of the artist. Photo courtesy Canadian War Museum.

The exhibition also includes art from Nancy Cole, Richard Johnson, Guy Lavigueur, Ivan Murphy, Kathryn Mussallem, Erin Riley and Eric Walker, each having been deployed somewhere in the world with Canada’s Armed Forces in 2014 or 2015. Styles and media include photography, paintings, sketches, video, and textiles.

Walker, another Ottawa-area artist, was deployed to CFB Stradacona in Halifax. His contribution to the show includes an aerial landscape of the military waterfront, cut from hundreds of tiny pieces of metal, and immediately recognizable to anyone familiar with Walker’s work.

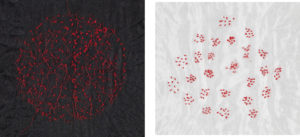

Nancy Cole (CFB Comox, on Vancouver Island) has a diptych of “conceptual, minimalist, hand-quilted textiles that address the dark and light aspects of the CF-18 Hornet’s role.” The large quilts are titled Day and Night. Day is a pearlescent white, like clouds seen from above, with a cluster of small red dots near the top. Cole describes the red cluster as a vanishing point, and there’s another in Night, where “18,000 stitches of black contrails disappear” into it.

Night and Day (detail), 2016, by Nancy Cole. Quilted textile. From the collection of the artist. Photo courtesy Canadian War Museum.

The quilts are in thoughtful contrast with the photography and realist portraiture in the exhibition, including Richard Johnson’s illustrative scenes of soldiers at work in the Ukraine. His pencil sketch of Canadian and Ukrainian soldiers in the routine action of disconnecting a tow cable suggests a reverse image of Joe Rosenthal’s iconic photo of U.S. Marines raising the American flag over Iwo Jima. The two images are vastly separated by decades and circumstance, yet that allusion, intentional or not, is itself a comment about the constancy of official war art. War art programs remain an essential insight into an eternal march of conflict, even as the art changes with the times.

A short side note: In the next gallery is She Who Tells A Story, which opened in December and has been written about before on artsfile.ca but deserves another mention. It includes 85 photographs from 12 female artists from Iran and the Arab world, all of which “challenge Western conceptions” about the Middle East. The emotions range from sorrow and despair to sensuality and humour. Together, they are as memorable as any art exhibition at the War Museum in years. “She” tells the story unforgettably.

Canadian Forces Artists Program — Group 7 continues to April 2. She Who Tells A Story closes March 4.